Dr Talia Cohen Solal sits down at a microscope to look closely at human brain cells grown in a petri dish.

“The brain is very subtle, complex and beautiful,” she says.

A neuroscientist, Dr Cohen Solal is the co-founder and chief executive of Israeli health-tech firm Genetika+.

Established in 2018, the company says its technology can best match antidepressants to patients, to avoid unwanted side effects, and make sure that the prescribed drug works as well as possible.

“We can characterise the right medication for each patient the first time,” adds Dr Cohen Solal.

Genetika+ does this by combining the latest in stem cell technology – the growing of specific human cells – with artificial intelligence (AI) software.

From a patient’s blood sample, its technicians can generate brain cells. These are then exposed to several antidepressants, and recorded for cellular changes called “biomarkers”.

This information, taken with a patient’s medical history and genetic data, is then processed by an AI system to determine the best drug for a doctor to prescribe and the dosage.

Although the technology is currently still in the development stage, Tel Aviv-based Genetika+ intends to launch commercially next year.

An example of how AI is increasingly being used in the pharmaceutical sector, the company has secured funding from the European Union’s European Research Council and European Innovation Council. Genetika+ is also working with pharmaceutical firms to develop new precision drugs.

The company hopes its work will be in strong demand in the future. There are more than 280 million people globally who suffer from depression, according to the World Health Organization.

And while taking antidepressants certainly won’t be the correct treatment for all, it has long been estimated that almost two thirds of initial prescriptions for depression or anxiety may not work properly.

“We are in the right time to be able to marry the latest computer technology and biological technology advances,” says Dr Cohen Solal.

Dr Heba Sailem says that the potential for AI to transform the global pharmaceutical industry, which generated revenues of $1.4 trillion (£1.1tn) in 2021, is huge.

A senior lecturer of biomedical AI and data science at King’s College London, she says that AI has so far helped with everything “from identifying a potential target gene for treating a certain disease, and discovering a new drug, to improving patient treatment by predicting the best treatment strategy, discovering biomarkers for personalised patient treatment, or even prevention of the disease through early detection of signs for its occurrence”.

Yet fellow AI expert Calum Chace says that the take-up of AI across the pharmaceutical sector remains “a slow process”.

“Pharma companies are huge, and any significant change in the way they do research and development will affect many people in different divisions,” says Mr Chace, who is the author of a number of books about AI.

“Getting all these people to agree to a dramatically new way of doing things is hard, partly because senior people got to where they are by doing things the old way.

“They are familiar with that, and they trust it. And they may fear becoming less valuable to the firm if what they know how to do suddenly becomes less valued.”

However, Dr Sailem emphasises that the pharmaceutical sector shouldn’t be tempted to race ahead with AI, and should employ strict measures before relying on its predictions.

“An AI model can learn the right answer for the wrong reasons, and it is the researchers’ and developers’ responsibility to ensure that various measures are employed to avoid biases, especially when trained on patients’ data,” she says.

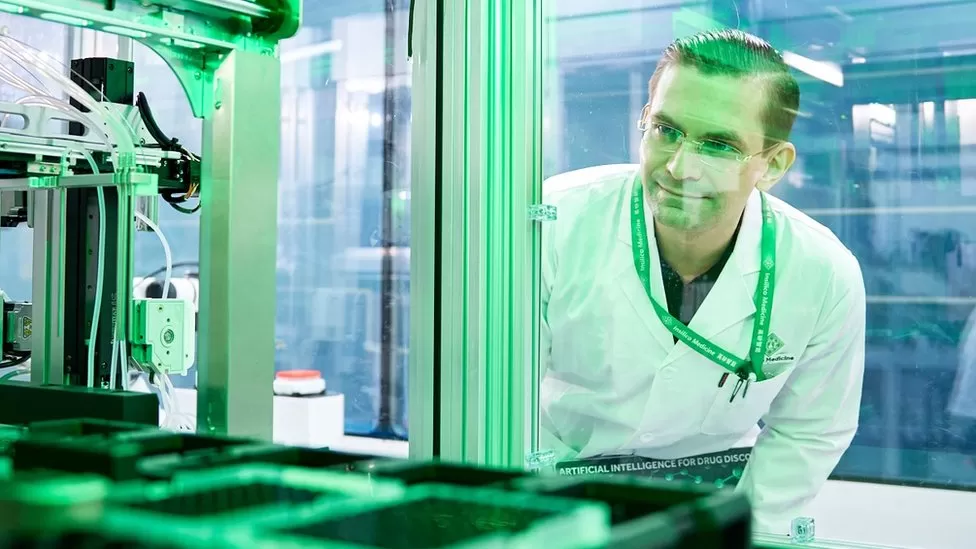

Hong Kong-based Insilico Medicine is using AI to accelerate drug discovery.

“Our AI platform is capable of identifying existing drugs that can be re-purposed, designing new drugs for known disease targets, or finding brand new targets and designing brand new molecules,” says co-founder and chief executive Alex Zhavoronkov.

Its most developed drug, a treatment for a lung condition called idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, is now being clinically trialled.

Mr Zhavoronkov says it typically takes four years for a new drug to get to that stage, but that thanks to AI, Insilico Medicine achieved it “in under 18 months, for a fraction of the cost”.

He adds that the firm has another 31 drugs in various stages of development.

Back in Israel, Dr Cohen Solal says AI can help “solve the mystery” of which drugs work.